Back in mid-September I started a seasonal job working the local hay and corn harvests here on our little spur of the Blue Ridge Mountains. It’s been long hours of hard physical labor most days, which is why I haven’t been writing much here. My apologies for the lack of content over recent weeks.

When I started this job I had zero tractor experience. Now I get why people are really into driving tractors. Hydraulics are an amazing invention.

The research has continued in the background, however, albeit at a slower pace than usual. I’ve been putting time in during the wee hours of the morning working on a paper with a couple of colleagues with the working title, “Predicting micropollutant breakthrough in carbon-based adsorbers from water quality and adsorbate parameters with and without rapid small column testing.”

We have compiled the largest database to-date of studies with biochar or GAC that include RSSCT data paired with pilot column or full-sized system data. We applied single and multiple linear regression analysis to this database of about 175 unique adsorbent-water-micropollutant combinations. This produced several expressions than can be used to predict full-sized biochar water treatment system performance (1) from RSSCT data alone, (2) from RSSCT data in combination with water quality and/or physical-chemical properties of target micro pollutants, or (3) from water quality and phys-chem parameters alone.

There are a lot more biochar adsorption studies done at the lab bench scale than at full scale because of the time, cost, and difficulty associated with full-scale studies. This work will allow us to project expected full-scale performance from a wide array of laboratory data. It will also allow us to estimate full-scale performance for target compounds and treatment scenarios where lab data are unavailable. These tools will be really powerful for us to gain the best available understanding of biochar water treatment system performance over an array of conditions.

We’re putting the finishing touches on the paper this week and next and plan to submit it for peer review soon.

And I’ve begin sketching out the plan for the next paper, which is the last link in the chain between the foundational theory, concepts, and empirical research on biochar adsorption and a set of user-oriented design-operation-monitoring tools for biochar water treatment practitioners. Connecting all those dots is going to be a really fun and gratifying exercise.

The corn harvest is winding down now as winter draws near, and I am looking forward to returning to research and writing full-time in the weeks ahead. The coming months are going to be very productive getting publications out and cranking out book sections.

I also wanted to share briefly about my developing philosophy of a two-pronged approach to, for lack of a better term, “global sustainable development,” and how my work during the fall harvest season fits into that.

I began Chapter 1 explaining a concept I’ve named the Imperial Wealth Pump and Waste Dump. I used this concept to contextualize recent trends under economic globalization of the transfer of chemical production, use, and pollution from developed countries to the poorer areas of the world:

Under this system, cheap labor (often child labor) in developing countries is exploited to extract natural resources to provide raw materials for the manufacture of Western consumer goods. Examples include the rare earth elements and minerals like coltan necessary for the manufacture of tech devices such as smartphones and laptops, and agrichemical-intensive plantation crops grown for export. Industries that make pharmaceuticals and other chemical products are sited in locales with permissive policies regarding pollution and politically disenfranchised local laboring classes. At the risk of stating a tautology, the majority of the benefits of consumer products and services are enjoyed by the affluent, whereas the costs are borne by others. Used-up consumer products are frequently “recycled,” which sadly is often just a euphemism for “dumped in poor communities to salvage what they can.” Notable examples of this practice are e-waste dumpsites in Africa, China, and South Asia, and the “donating” of obsolete pesticides (stockpiles of chemicals that were banned in developed countries due to their environmental persistence, toxicity, and tendency to bioaccumulate) to African countries as “development assistance.”

I initially took the time to lay all this out because, until very recently, exposure to chemical toxicants was completely overlooked in the water-sanitation-hygiene (WASH) sector. I went to a lot of trouble to make the case that chemicals are, in fact, incredibly important in WASH. The Imperial Wealth Pump and Waste Dump framework came into view as a by-product of the massive effort I undertook to document the impact of chemicals on WASH and health.

And of course, the concept applies to much more than chemical production, use, disposal, water pollution, and human exposure. You can go sector by sector - energy, climate, agriculture, forestry, transportation, the built environment, industry, mobile and internet technologies, finance and banking, and so on - and see examples of the IWP&WD at work. It operates between rich and poor countries, as well as within rich and poor zones within countries and regions.

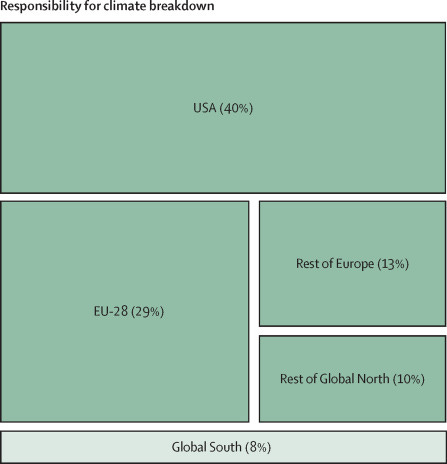

The IWP&WD accumulates wealth, status, power, and affluence for a global minority - the top 10 or 15% in socio-economic status - by exploiting and impoverishing the poor, extracting resources at unsustainable rates, polluting the environment, destabilizing the climate, ravaging ecosystems and extinguishing biodiversity. For example, anthropologist Jason Hickel estimates that affluent/wealthy regions are responsible for 92% of global climate breakdown, while the poor (the “Global South”) collectively are only responsible for 8% but suffer most of the consequences.

Responsibility for excess greenhouse gas emissions leading to climate breakdown. Source: Jason Hickel, 2020.

I have come to see poverty and affluence as fundamentally interdependent phenomenon - to create affluence in one place necessitates creating poverty somewhere else. Wouldn’t it be great if we could all be affluent, high status professionals! Well it isn’t possible bio-physically for this many people on only one planet. And it isn’t even possible theoretically since you’d only know you were affluent and high status if there were poor, low status people somewhere else to compare with.

It might seem odd at first to identify affluence as a problem. Poverty? Sure. Most everyone is in favor of eliminating poverty, in some cases even to the point of declaring a “war on poverty,” as former US President Lyndon Johnson did in the 1960’s after visiting my native home of Appalachia and witness the living conditions of coal miners’ families. But the affluence of the global minority at the top of the socio-economic hierarchy is in fact the root of much of our social and environmental ills in the 21st Century. I’m not talking about just “the 1%” as identified by the Occupy Wall Street movement, but the top 10 to 15% globally in term of income, status, and privilege. Us college-educated, professional, cosmopolitan, “middle-class” folk, in other words.

The flows of energy and resources needed to sustain our affluent personal and professional lifestyles coupled with the need to exploit cheep labor and find places to dump harmful wastes and the violence or threat of violence imposed by the Military-Industrial-Complex needed to keep this unjust system in place are the fundamental barriers preventing authentic “global sustainable development.” Scientists writing in Nature Communications last year summarized:

“The affluent citizens of the world are responsible for most environmental impacts and are central to any future prospect of retreating to safer environmental conditions. … Any transition towards sustainability can only be effective if far-reaching lifestyle changes complement technological advancements.”

Wiedmann et al., Nature Communications volume 11, Article number: 3107 (2020).

When I was a university professor and working in the professional sector of WASH and “global sustainable development,” I experienced the disturbing awareness that the very same processes that generated the affluence and status I enjoyed were driving the problems of poverty and pollution I was trying to “solve” through the application of technology. Even if I could “do some good” through a particular “sustainable WASH intervention,” I was still enmeshed in and totally dependent upon the IWP&WD dynamic that causes poor WASH circumstances in the first place. I couldn’t shake the concern than this existential contradiction negates most or all of the potential good done through the professional approach to “global sustainable development.”

This led me to slowly work out a two-pronged approach to, what I hope, is an authentic path to sustainability, equality, and peace. One prong reaches out into the world, working in service to impoverished communities to assist in the implementation of beneficial interventions. The other prong reaches inward, towards home.

The intervention prong operates at the grassroots level, in contrast to the rarefied level of the professional development technocrat. I’ve written about the grassroots approach here previously, and plan to continue along this trajectory throughout my lifetime.

The second prong is a harm reduction approach. If the affluent professional is hemmed in by dependence on a globalized economic system that exploits people and ecosystems at the other end, then a harm reduction strategy progressively breaks these dependencies, thereby alleviating pressures on far-flung ecosystems and the poor.

What does that look like in practice? Well, I think there can be many versions of enacting a harm reduction approach to life and work. The version that I am working out has involved my wife and I returning to our native Appalachia and working collaboratively towards building a regenerative and equitable bioregional economy. If we can meet progressively more of our needs through our own efforts at sustainable management of local resources, we lessen our dependence on exploitive globalized systems and reduce the harm those systems do to others, elsewhere. That’s the principle, anyway.

With this framework in mind, my participation in the fall harvest activities makes sense, perhaps. We moved here in March, 2020, right as the first wave of COVID was spreading throughout the US and social distancing policies were implemented. Accordingly, it was difficult to meet people and make connections. But over the past two months I’ve become much more integrated in the local community. I have gained a lot of new skills and knowledge from working alongside our rural mountain neighbors. I have access to resources and equipment that have been invaluable to our own farm projects. If all goes well, we will get a great portion, possibly 80% or more, of the winter feed we need for our animals from farms within a few miles radius of our place. This is a huge leg-up as our Shetland wool and pastured pork projects gain steam. All our heat and hot water this winter will be supplied by wood we cut on our land, as we manage our small forest for energy, forage foods, wood and stone building materials, and wildlife habitat. These are some of the things we’re doing to build resilience and reduce our dependence on globalized, mass-produced consumer goods, fossil fuels, and the industrial ag system that causes so many environmental problems and so much animal suffering. And we couldn’t do it without our neighbors.

A happy, healthy, handsome Shetland ram.

The COVID pandemic has laid bare the vulnerability and fragility of a highly interconnected, globalized economy and dependencies on long supply chains for basic goods. I’ve been saying for years, prior to COVID, that a turn towards greater local and bio-regional self-reliance (not isolationism) is prudent. We can build our own resilience while decreasing our dependence on exploitive and ecologically destructive systems in a win-win strategy. And we don’t have to wait on governments or Silicon Valley or “the free market” to act.

Working out how to do this in a practical sense is my rest-of-life project. Biochar water treatment has been the most detailed and interesting chapter of that project so far. I will keep pushing that out into the world, but I am really looking forward to whatever new adventures await. I’m thinking about spinning off a substack site to document the journey once this book is done, if there is sufficient interest.

Anyway, thanks for indulging me. More nerdy biochar adsorption content to come thick and fast soon, I promise…

I'd be interested in your other writing when the time comes, we're trying to follow a similar path here with our homestead farm in the Philippines.